When people think of Victorian London, they often imagine grand architecture, horse-drawn carriages, and the elegance of the British Empire at its peak. But in the autumn of 1888, just a short walk east from the gleaming spires of the City of London, a very different world existed.

Whitechapel in 1888 was a place of crushing poverty, overcrowded lodging houses, and desperate lives. It was here, in these dark, narrow streets, that Jack the Ripper would carry out the most infamous murders in British criminal history. But to truly understand these crimes, you first need to understand the world in which they occurred.

A District of Desperate Poverty

By the late 1880s, Whitechapel had become one of the most impoverished areas in all of London. The district sat just outside the ancient walls of the City, and for centuries it had served as a refuge for those who could not afford to live within.

Charles Booth, the social researcher who famously mapped London’s poverty in the 1880s, coloured much of Whitechapel in black and dark blue – the shades indicating “very poor” and “semi-criminal” populations. The streets around Flower and Dean Street were described by police as “perhaps the foulest and most dangerous street in the whole metropolis.” Dorset Street, where Jack the Ripper’s final victim Mary Jane Kelly lived, earned the grim title of “the worst street in London.”

The Yiddish theatre actor Jacob Adler, writing of his arrival in Whitechapel in 1883, recalled: “Never in Russia, never later in the worst slums of New York, were we to see such poverty as in the London of the 1880s.”

Life in the Lodging Houses

For the poorest residents of Whitechapel, home was often a “doss house” – a common lodging house where you could rent a bed for fourpence a night. These establishments packed dozens of beds into cramped, airless rooms. Men and women slept in close quarters with strangers, with no privacy and precious little security.

The conditions were appalling. Damp walls, infestations of vermin, and the stench of unwashed bodies made these places barely habitable. Yet for many, the alternative was sleeping rough in doorways or under railway arches.

All five of Jack the Ripper’s canonical victims – Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly – were residents of these lodging houses at various points in their lives. On the night of her death, Mary Ann Nichols had been turned away from her lodgings because she lacked the fourpence for a bed. “I’ll soon get my doss money,” she reportedly said. “See what a jolly bonnet I’ve got now.” Within hours, she would be dead.

The Streets After Dark

Walking through Whitechapel in 1888, particularly after nightfall, was to enter a world of shadows and danger. The narrow courts and alleyways were lit only by gas lamps, which cast pools of dim, flickering light that barely penetrated the gloom. Dense fog – the famous London “pea-soupers” caused by coal smoke mixing with moisture – could reduce visibility to just a few feet.

The layout of the streets themselves aided concealment. Whitechapel was a maze of interconnected passages, yards, and courts. Many thoroughfares had multiple entrances and exits, allowing someone to disappear quickly. The murder sites chosen by Jack the Ripper – Buck’s Row, Hanbury Street, Berner Street, Mitre Square, and Miller’s Court – were all secluded spots where a crime could be committed with minimal risk of observation.

Police patrols were stretched thin. Beat constables walked regular, timed routes, and local criminals knew exactly when officers would pass. There were even parts of Whitechapel that police were reluctant to enter at all.

A Community of Immigrants

Whitechapel in 1888 was one of the most diverse areas of London. The district had long been a first stopping point for immigrants arriving in Britain, and by the late Victorian era, its population was a complex mix of nationalities and cultures.

The largest immigrant community was Jewish, fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe and Russia. Thousands of Jewish refugees had settled in Whitechapel, establishing tailoring workshops, synagogues, and a vibrant Yiddish-speaking culture. By 1888, the Jewish community dominated much of the local tailoring industry.

This diversity contributed to social tensions. Anti-immigrant sentiment was common, and when the Ripper murders began, suspicion quickly fell on “foreigners.” A man known as “Leather Apron” became an early suspect, and the press reported that he was a Jewish bootmaker. When graffiti reading “The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing” was found near one murder scene, police hastily erased it, fearing it would spark anti-Jewish riots.

Prostitution and Survival

In October 1888, the Metropolitan Police estimated that there were approximately 1,200 prostitutes “of very low class” working in Whitechapel, along with 62 brothels. These figures were almost certainly underestimates.

For many women in Whitechapel, prostitution was not a choice but a necessity. With few employment options available, and those that existed – such as matchbox making or sewing – paying starvation wages, selling sex was often the only way to afford food and lodging. A woman might earn threepence for an encounter – just enough for a bed and perhaps a drink to dull the misery of her circumstances.

All five of the Ripper’s canonical victims had, at various times, worked as prostitutes. They ranged in age from 25 to 47, and all struggled with alcohol dependency – a common means of coping with the harsh realities of life in the East End. The heavy drinking and rough living aged these women prematurely; contemporary accounts describe women in their forties looking decades older.

The Pubs and Music Halls

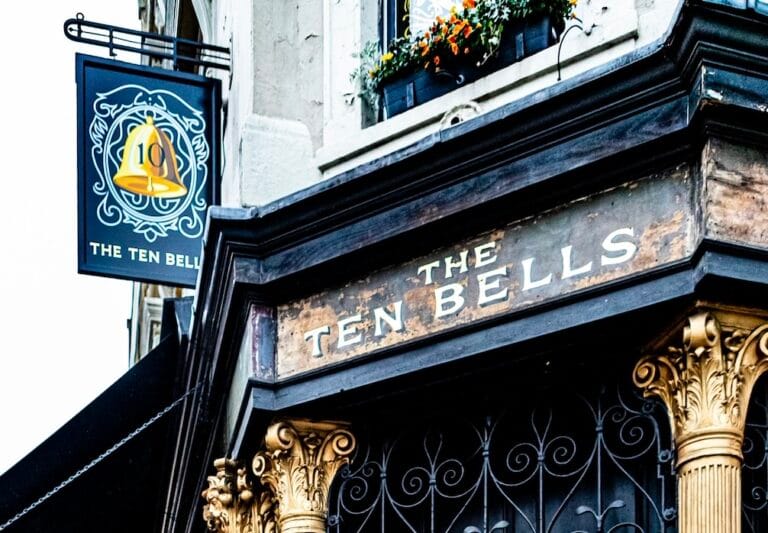

Despite the grinding poverty, Whitechapel was not without its entertainments. Public houses stood on almost every corner, offering cheap gin and beer to those seeking escape from their daily struggles. The Ten Bells pub on Commercial Street, which still stands today, was frequented by several of the Ripper’s victims.

Music halls provided another form of escape, offering variety shows, comedy acts, and popular songs. For a few pennies, working-class Londoners could forget their troubles for an evening. The area around Whitechapel Road was home to several such establishments, their bright lights and raucous laughter providing a stark contrast to the darkness of the surrounding streets.

When Terror Gripped the Streets

The Jack the Ripper murders, which occurred between August and November 1888, sent shockwaves through Whitechapel and beyond. The brutal nature of the crimes – victims found with their throats cut and their bodies mutilated – created a atmosphere of genuine terror.

Women were afraid to walk the streets alone. Vigilance committees were formed by local residents determined to catch the killer. The press coverage was unprecedented, with newspapers across the country and around the world reporting on every development. Letters poured in to Scotland Yard and the press, many from people claiming to be the murderer.

It was this intense media attention that transformed a series of local murders into an international phenomenon. The name “Jack the Ripper” – coined in a letter received by the Central News Agency, likely written by a journalist rather than the killer – gave the unknown murderer a identity that would endure for more than a century.

A Catalyst for Change

The Whitechapel murders had an unexpected consequence: they forced affluent Victorian society to confront the appalling conditions in which the East End poor lived. Journalists who came to report on the crimes found themselves writing about the poverty, overcrowding, and social neglect they witnessed.

George Bernard Shaw, writing to The Star newspaper in September 1888, noted with bitter irony: “Whilst we conventional Social Democrats were wasting our time on education, agitation and organisation, some independent genius has taken the matter in hand, and by simply murdering and disembowelling… women, converted the proprietary press to an inept sort of communism.”

In the years following the murders, Parliament passed legislation including the Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890, which set minimum standards for accommodation. Slum clearance programmes began, and gradually the worst of Whitechapel’s rookeries were demolished.

Whitechapel Today

Walking through Whitechapel today, it can be difficult to imagine the squalor and desperation of 1888. The slums have long since been replaced by modern buildings, and the area has undergone waves of regeneration. Yet traces of the Victorian East End remain.

Some of the streets the Ripper walked still exist, though often under different names – Buck’s Row is now Durward Street, and Berner Street has become Henriques Street. Victorian buildings survive here and there, their weathered brickwork a tangible link to the past. The Ten Bells pub still serves customers, and Christ Church Spitalfields still towers over the area as it did in 1888.

The best way to understand what Whitechapel was really like in 1888 is to walk its streets with an expert guide who can point out what remains and help you visualise what has been lost. Standing in the quiet courtyards and narrow passages where the murders occurred, it becomes possible to glimpse the world that Jack the Ripper and his victims inhabited – a world of shadows, poverty, and fear that still has the power to fascinate and horrify us more than 130 years later.

Experience Victorian Whitechapel for Yourself

Our Jack the Ripper walking tour takes you through the streets and alleyways where these infamous crimes took place. Led by expert guides, you’ll visit the actual murder sites, see surviving Victorian architecture, and gain a deeper understanding of life in 1888 Whitechapel. It’s not just a tour about murder – it’s a journey into a vanished world.

Frequently Asked Questions

How poor was Whitechapel in 1888?

Whitechapel was one of the most impoverished areas in Victorian London. Charles Booth’s poverty maps marked much of the district as “very poor” or “semi-criminal.” Many residents lived in overcrowded lodging houses, paying fourpence a night for a bed. The poverty was so severe that contemporary observers compared it unfavourably to slums in Russia and New York.

Why did Jack the Ripper choose Whitechapel?

Whitechapel’s maze-like streets, poor lighting, stretched police resources, and vulnerable population of women working as prostitutes made it an ideal hunting ground. The area’s numerous courts and alleyways provided concealment, while poverty meant potential victims were often out on the streets late at night seeking to earn money for lodgings.

What was Dorset Street like in 1888?

Dorset Street was known as “the worst street in London.” It was home to numerous lodging houses and was a centre of prostitution and crime. Mary Jane Kelly, the Ripper’s final victim, lived in a small room in Miller’s Court, just off Dorset Street. The street was later demolished as part of slum clearance programmes.

Can you still see Victorian Whitechapel today?

While much of Victorian Whitechapel has been rebuilt, some original features survive. Several streets still follow their 1888 routes (though often renamed), Victorian buildings remain scattered throughout the area, and landmarks like Christ Church Spitalfields and the Ten Bells pub still stand. A guided walking tour is the best way to discover these surviving traces of the past.