The five canonical victims of Jack the Ripper weren’t just statistics in Victorian crime records—they were real women with real addresses, living in one of London’s most desperate neighborhoods. Understanding where these women lived reveals as much about the Ripper case as the crimes themselves.

Why Their Addresses Matter

In 1888, Whitechapel wasn’t just poor—it was catastrophically overcrowded. The victims’ addresses tell us about the lodging house system, the economic desperation that made women vulnerable, and why the Ripper’s hunting ground was so concentrated.

When you see where Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly lived, you realize they all existed within roughly half a square mile. This wasn’t coincidence—it was circumstance.

Mary Ann Nichols: 18 Thrawl Street

Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols was the first canonical victim, murdered on August 31, 1888. At the time of her death, she’d been staying at 18 Thrawl Street, a common lodging house just off Brick Lane.

Thrawl Street still exists today, though the Victorian buildings are long gone. Common lodging houses—essentially Victorian homeless shelters—charged 4 pence per night for a bed. On the night Polly died, she’d been turned away for not having her doss money. She was last seen alive at 2:30 AM, walking toward Buck’s Row (now Durward Street) where her body was discovered less than an hour later.

What it tells us: The proximity between her lodging and murder site—less than a 10-minute walk—shows how small the victims’ world really was. When you couldn’t afford your bed, you walked the streets until dawn or earned your doss money however you could.

Annie Chapman: 35 Dorset Street

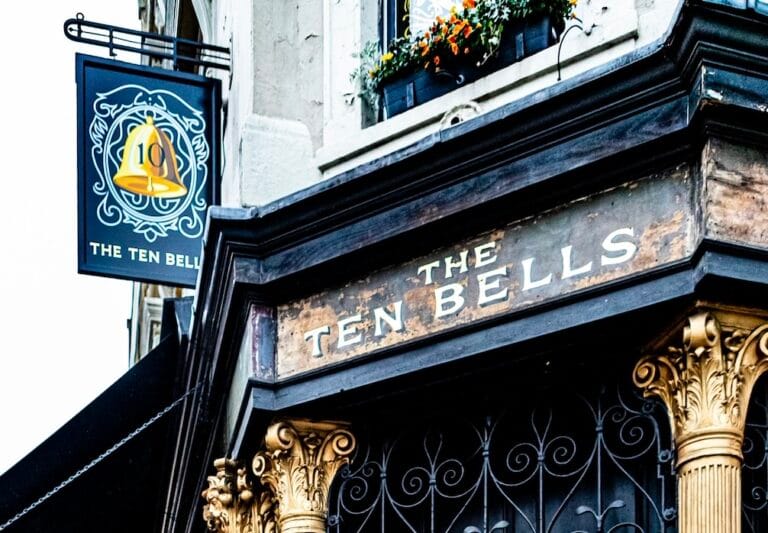

Annie Chapman, murdered September 8, 1888, lived at Crossingham’s Lodging House at 35 Dorset Street. If Thrawl Street was rough, Dorset Street was infamous—known as “the worst street in London.”

Like Polly, Annie was turned away on the night of her murder for lacking the 8 pence for her bed (prices varied by lodging house). The deputy saw her leave around 1:45 AM. Her body was found at 6 AM in the backyard of 29 Hanbury Street—a straight 5-minute walk from Dorset Street.

Dorset Street no longer exists; it was demolished in the 1920s and is now covered by the modern white buildings of the Whites Row Estate. But walking through this area today, you can still sense the narrow passages and enclosed yards that made Victorian Whitechapel so dangerous after dark.

What it tells us: The Ripper knew this area intimately. The backyard at Hanbury Street was accessed through a passage in a multi-occupancy building—not somewhere a stranger would stumble upon by chance.

Elizabeth Stride: 32 Flower and Dean Street

Elizabeth Stride was murdered on September 30, 1888—the night of the “double event” when two women died within an hour. She’d been living at 32 Flower and Dean Street, another common lodging house in what was perhaps Whitechapel’s most notorious street.

Flower and Dean Street was so crime-ridden that it appears repeatedly in Victorian social reform literature. Charles Booth’s poverty maps colored it black—the worst rating possible. Elizabeth’s body was found in Dutfield’s Yard off Berner Street (now Henriques Street), again just a few minutes’ walk from her lodging.

Today, Flower and Dean Street has been completely redeveloped and renamed Lolesworth Close. Council estates stand where the lodging houses once packed in hundreds of desperate people each night.

What it tells us: The “double event” happened because the Ripper was likely interrupted with Elizabeth Stride. He then walked just 12 minutes southeast to Mitre Square and killed Catherine Eddowes. Both locations were within his comfort zone.

Catherine Eddowes: 55 Flower and Dean Street

Catherine Eddowes, the second victim of the double event, also lived on Flower and Dean Street—number 55, just doors away from Elizabeth Stride. This wasn’t unusual; many of the victims knew each other or shared the same lodging houses.

Catherine had actually been in police custody earlier that night, arrested for being drunk and disorderly. She was released at 1:00 AM and murdered in Mitre Square by 1:45 AM. The speed of this attack, combined with the extensive mutilations, has led many Ripperologists to believe the killer was indeed interrupted with Stride and took out his frustration on Eddowes.

Mitre Square still exists today and looks remarkably similar to 1888—one of the few Ripper locations where you can genuinely stand where history happened.

What it tells us: Two victims living on the same street reinforces how small and interconnected this community was. Everyone knew everyone, yet the Ripper remained anonymous.

Mary Jane Kelly: 13 Miller’s Court

Mary Jane Kelly’s address is perhaps the most haunting because unlike the others, she wasn’t killed on the street—she was murdered in her own room at 13 Miller’s Court, off Dorset Street.

This single room, roughly 12 feet square, was where the Ripper committed his most savage attack. Because he had privacy and time, the mutilations were extensive. She was found on the morning of November 9, 1888.

Miller’s Court no longer exists. It was demolished in the 1920s, and the area is now a car park behind what used to be Spitalfields Market. A small section of Dorset Street remains as Duval Street, but the court itself is gone entirely.

What it tells us: Mary Jane was the only victim killed indoors, leading some to believe the Ripper either knew her personally or that this was an escalation—he’d grown bold enough to follow a victim inside. The fact that she had her own room (not just a bed in a dormitory) suggests she was slightly better off than the other victims, though still desperately poor by any standard.

The Geography of Desperation

When you map these addresses, a pattern emerges. All five women lived within a half-mile radius. Their lodging houses clustered around Flower and Dean Street, Thrawl Street, Dorset Street, and Fashion Street—the absolute epicenter of Victorian poverty.

This wasn’t a coincidence. This was the only area where women in their circumstances could live. Rents elsewhere in London were beyond their means. The common lodging houses of Whitechapel represented the bottom rung of Victorian housing—one step above sleeping rough.

The Ripper didn’t need to hunt widely. His victims were contained by economics, trapped in a tiny area where desperation was the common currency.

Walking These Streets Today

Very little of 1888 Whitechapel remains physically intact. Thrawl Street has been rebuilt. Dorset Street was obliterated. Flower and Dean Street was renamed and redeveloped. But the street pattern is largely the same, and walking from address to address reveals just how compressed this world was.

Modern Whitechapel has transformed dramatically—now home to markets, street art, and the overspill of the City. But the echo of those Victorian streets remains in the tight alleyways, the sudden dark passages, and the proximity of everything to everything else.

If you want to understand the Jack the Ripper case, you need to understand the geography—not just of the murder sites, but of where these women lived their daily lives. The addresses weren’t just numbers. They were the coordinates of desperation in Victorian London’s most notorious square mile.